by Emily Burns, Ph.D | Sky Island Alliance

Thanks to our community partners, Sky Island Alliance, for providing this guest blog for Desert Diaries. Support their border conservation work by following them on social media, volunteering, and donating!

Standing at the foot of the border wall in southeast Arizona is intimidating. The wall rises 30 feet into the air and stretches east and west from horizon to horizon. It is literally a continental divide that significantly changes how wildlife moves between the U.S. and Mexico, impacting the health and genetic diversity of populations on both sides of the border. During my first visit to the border wall back in 2019, I saw javelina tracks that led right up to the base of the wall and stopped. Five years and 13,000 wildlife videos taken at the wall later, we now know what it takes to make the border wall more friendly for wildlife on the move and how to help species like javelina, coyote, and even mountain lion cross to the other side.

Sky Island Alliance and Wildlands Network operate a transect of motion-activated cameras that record what animals do along the border in southern Arizona. The cameras face the international boundary in habitats with border wall or vehicle barrier (low steel barricades that stop vehicles but not animals). Dozens of volunteers and undergraduate interns from the University of Arizona and Pima Community College have contributed hundreds of hours to the project. They help collect memory cards from the border cameras and turn each video into data on the species observed, number of animals in the frame, direction of movement, wildlife behavior next to border infrastructure, and confirmation if a successful border crossing occurs.

Our data are the first of their kind to show the direct impact of border infrastructure on wildlife movement (Harrity et al. 2024 Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution; 2). We found that many animals in border habitat appear to ignore the border itself and simply carry on with normal behaviors like grazing or roaming parallel to the border. However, 43% of wildlife do approach and interact with border infrastructure. More than half of those interactions result in animals unable to cross the border, failing to cross after investigating the border wall or vehicle barrier.

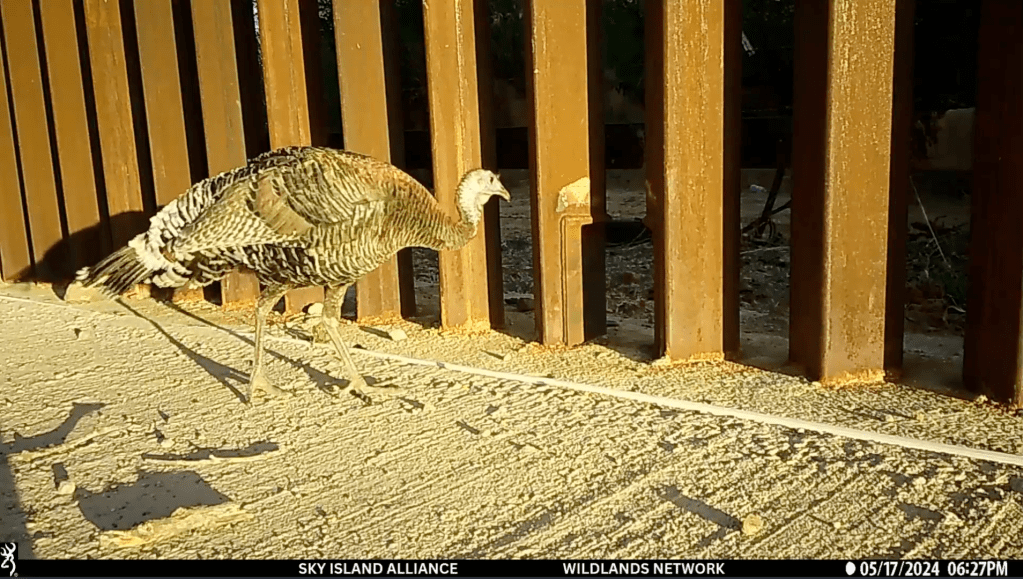

What’s fascinating to me is the animals that do cross between Arizona and Sonora successfully. We studied the crossing success rates for 20 large wildlife species including American black bear, mountain lion, white-tailed and mule deer, coyote, javelina, and turkey. When the border only has vehicle barrier, 65% of wildlife interactions with the border result in a successful crossing. It is only in these areas with vehicle barrier where bear, deer, and turkey can still move between the U.S. and Mexico – none of these species have been observed to navigate through border wall. In fact, only 9% of wildlife interactions with the border wall lead to crossing and this is only because smaller species like bobcat, hares and rabbits, raccoons, skunks, and foxes can squeeze between the 4-inch border wall bollards. When compared to vehicle barrier, successful wildlife crossings are 86% lower at border wall. Many animals are being stopped in their tracks by the wall.

Vehicle barriers, shown in the bottom three images, allow for greater wildlife connectivity and more successful crossings for bear, deer, and turkey. These screenshots are from Sky Island Alliance wildlife camera recordings. Watch the videos here.

Smaller animals like the bobcat and hog-nosed skunk above will sometimes squeeze through the 4-inch openings in the border wall.

The hope for reestablishing connectivity for many species at the wall is linked to the installation of wildlife crossing structures. There are 13 small wildlife openings installed in the border wall along the 70-mile continuous stretch of border wall in Arizona from the Huachuca Mountains eastward to the state line with New Mexico. These small openings are indeed small – they measure just 8.5 inches wide and 11 inches high. They are the size of a standard piece of printer paper. Amazingly, we discovered that javelina, mountain lion, and coyote are 16.7 times more likely to cross through border wall when they encounter one of these small openings, called “cat doors” by Border Patrol. While these small passageways will not allow bear, deer, turkeys, and humans to cross, they greatly improve connectivity between the U.S. and Mexico for many animals and now is a great time to install more along the border.

In the above images, wildlife cross through wildlife crossing structures, small openings in the wall that allow animals to squeeze through. From upper left to bottom right: coyote pups, javelina, raccoon, a solitary mountain lion, and a female mountain lion with three kittens following behind.

The southern border of the U.S. already has 636 miles of border wall and more wall will likely be built in the years ahead. I remain hopeful that our research will help inspire better design of the border wall to help more wildlife cross. We know that even the small openings help squadrons of javelina squeeze through the wall and nothing brings me more joy than to see a highway of animal tracks crossing through a passageway in the border wall. We intend to keep our cameras rolling, call for more and larger crossing structures in the border wall, and protect the remaining corridors that our iconic wildlife has used for millennia.

To learn more about the project, volunteer, or support the research, please visit our Border Wildlife Study webpage or contact me (emily@skyislandalliance.org).