Desert Museum Volunteers Build Barcode Reference Library of Native Bees

By Kim Franklin

Eight years ago I launched a small study of the native bee diversity in Las Mipiltas de Cottonwood, a small urban farm in Tucson, Arizona. With the help of a few intrepid volunteers, we began sampling bees every two weeks with pan traps, small cups painted blue, white, or yellow and filled with water. Attracted to the colorful cups, the bees land on the water and are unable to escape.

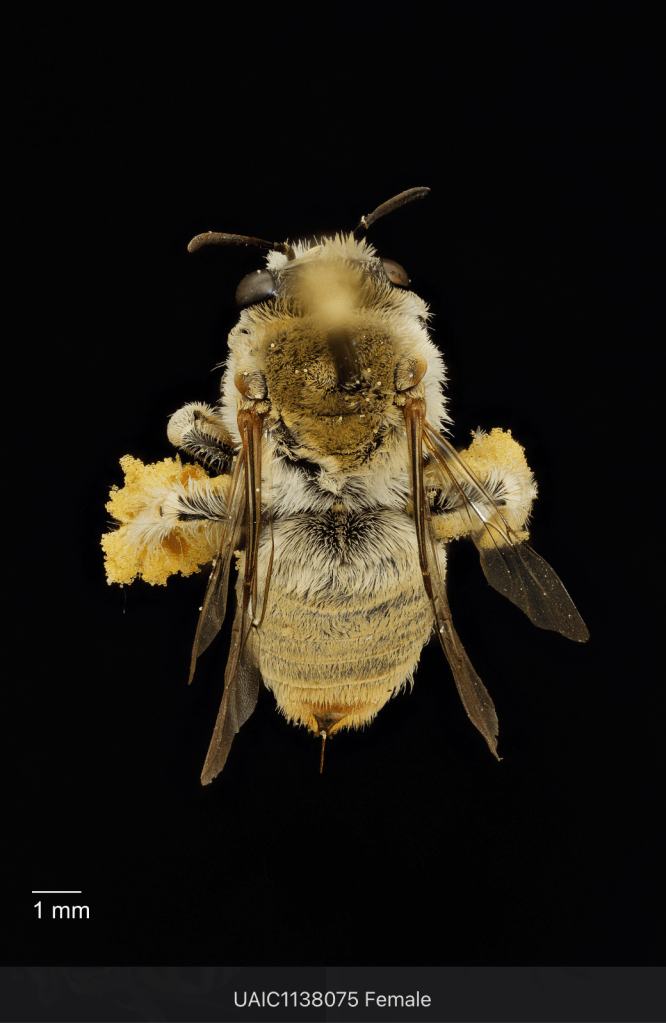

No scientist enjoys sacrificing the organisms they study, even for the sake of learning more about them. For the most part, data on vertebrates, such as birds and mammals, can be gathered without harming the animals. Unfortunately, this is not true of most insects. Closely related insect species are often distinguished from each other by tiny differences in their morphology (the form and structure of organisms), requiring careful examination under a microscope.

For example, two bees may appear nearly identical, but a careful examination of the exoskeleton under a microscope reveals that the subantennal sutures of one extend all the way to the clypeus while the subantennal sutures of the other do not. Complicating things further, some insect species can only be differentiated from each other by examining their internal morphology, while still others require DNA sequencing! Thus, in pursuit of expanding our knowledge of these incredibly diverse and intriguing creatures, scientists have needed to collect insects to properly study them.

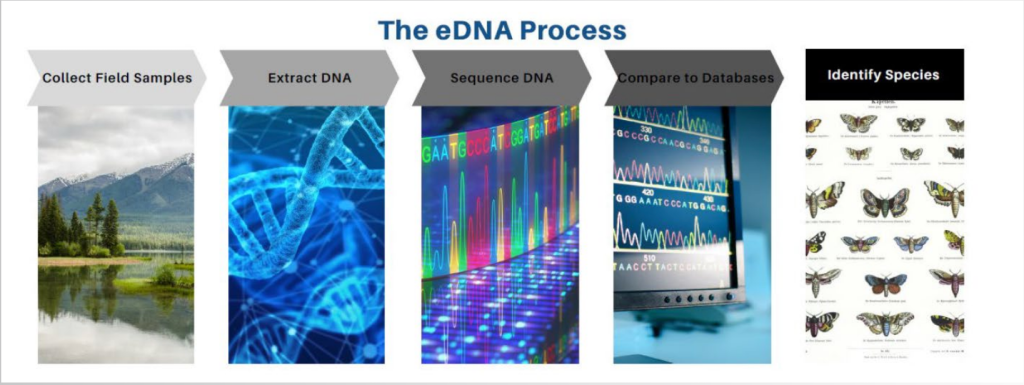

But this is changing with advances in our understanding of environmental DNA (eDNA)—the DNA naturally shed by organisms in the form of hair, feces, saliva, skin, and more, as they move through their environment. Researchers can collect eDNA from air, water, and soil, or from surfaces and structures such as a leaf, flower, burrow, or nest to determine the species present in and around these environments, much like a forensic scientist collecting DNA from a crime scene to identify the individuals who may have been present before, during, or after a crime.

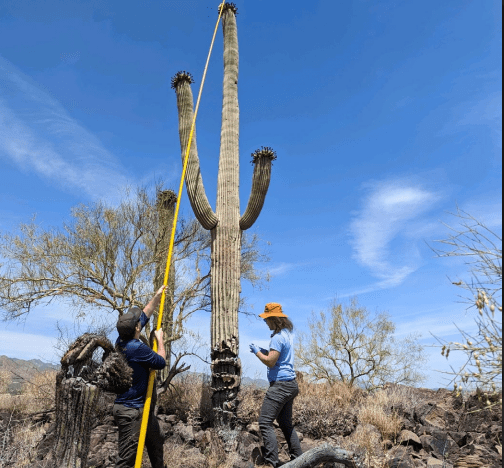

That’s exactly what a team of scientists, led by Mark Johnson, set out to do last May as they sampled eDNA from saguaro cactus flowers. They wanted to know if they could use eDNA to determine which animal species, including insects, birds, and bats, were visiting saguaro flowers in Tucson. They collected nearly 200 saguaro flowers across three sites: Tumamoc Hill, an urban site; Tucson Mountain Park, a wildland site; and the Desert Museum, neither urban nor wildland, but an unusual site with abundant water and exceptional plant diversity.

A long pole was used to knock saguaro flowers off the tops of saguaros, while an anxious catcher wearing sterile gloves waited below hoping to catch each flower before it hit the ground. Back in the makeshift lab that Mark and colleagues set up in their hotel room, they washed the eDNA from the flowers with a solution that would preserve the DNA until they could get it back to their lab in Illinois. Back home, they applied a technology called metabarcoding to sequence the many strands of DNA from many different species, all at the same time. Metabarcoding is a more advanced form of DNA barcoding, a powerful technology that enables the identification of a species by the unique sequence of a short section of DNA in its genome, known as a barcode. Scientists are building libraries of reference barcodes, with the goal of including a reference barcode for every species on earth.

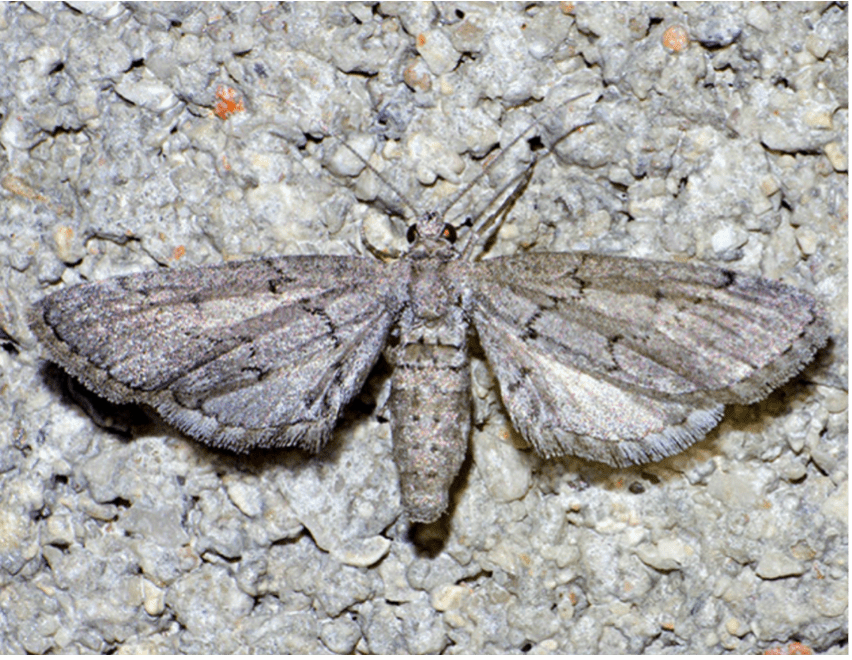

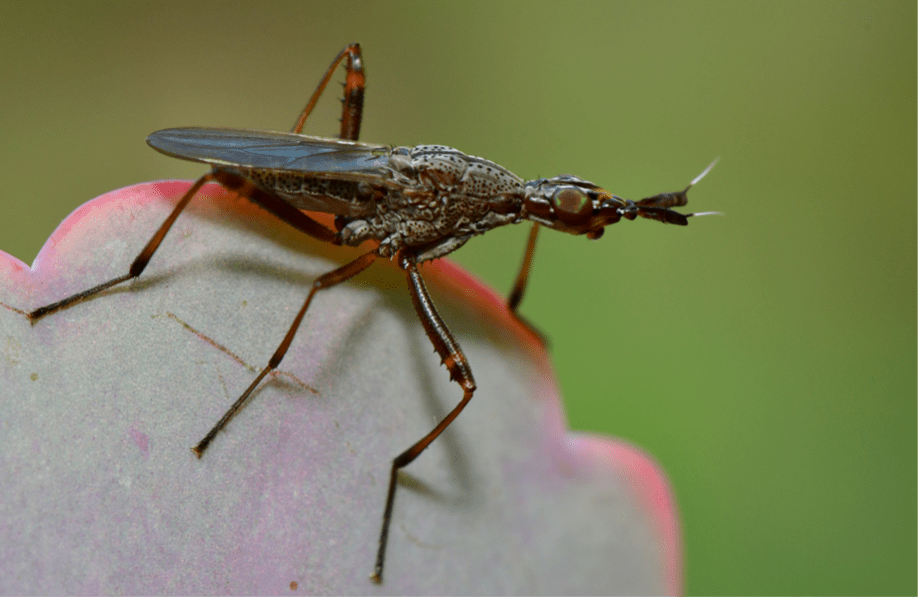

Sequencing just the arthropod DNA washed from the saguaro flowers resulted in a total of 672,453,977 sequences! Thus far, we’ve matched 12% of those 672 million sequences to a total of 66 species. Species common across all three sites included one wasp and one thrips species, several fly species, the honey bee, a hairstreak butterfly and a geometrid moth.

We know the saguaro, a keystone species, plays an essential role in supporting diverse insect communities, and certainly many more species await to be discovered as we work through the remaining 590 million sequences more carefully. This promising research not only represents a turning point in our understanding of Sonoran Desert insect communities, it also illustrates the importance of species identification.

It’s striking that 590 million sequences did NOT match to any species. While many failed to match due to low sequence quality (eg. the sequence was too short or contained too many gaps), undoubtedly many other sequences failed to match due to the lack of a reference barcode in the barcode library. Successful species identification through metabarcoding depends on the existence of a reference library of known barcodes coming from specimens that have been identified to species by experts.

This brings us full circle to the study of native bee diversity in Las Milpitas that began in 2016. Since then, over a dozen volunteers have joined the research team, we’ve added three additional study sites, and we’ve grown our collection to over 20,000 bees. Every single bee we’ve collected has been carefully pinned, labeled, and identified to genus, all by our volunteers!

The bottleneck in our work is species identification. Knowing the genus to which a bee belongs gives you a lot of information about its evolutionary history, but species identification is essential to conservation efforts because even closely related species can differ greatly in their ecology. For example, two species in the same genus may have very different habitat requirements and thus conservation efforts for one species may not benefit the other.

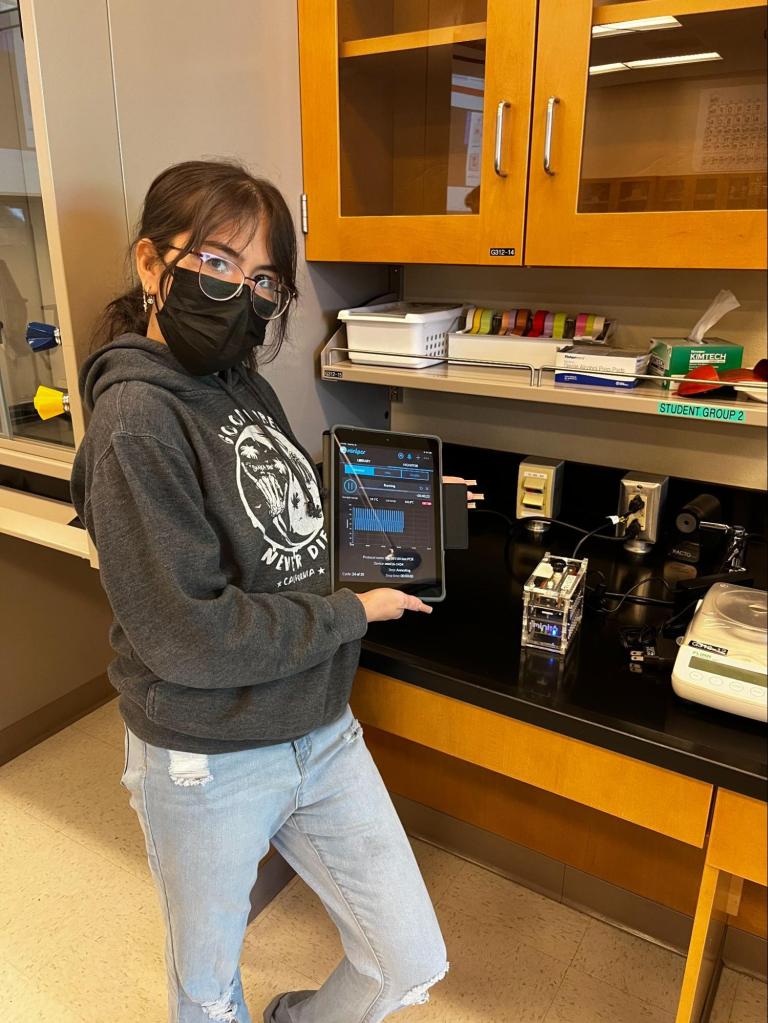

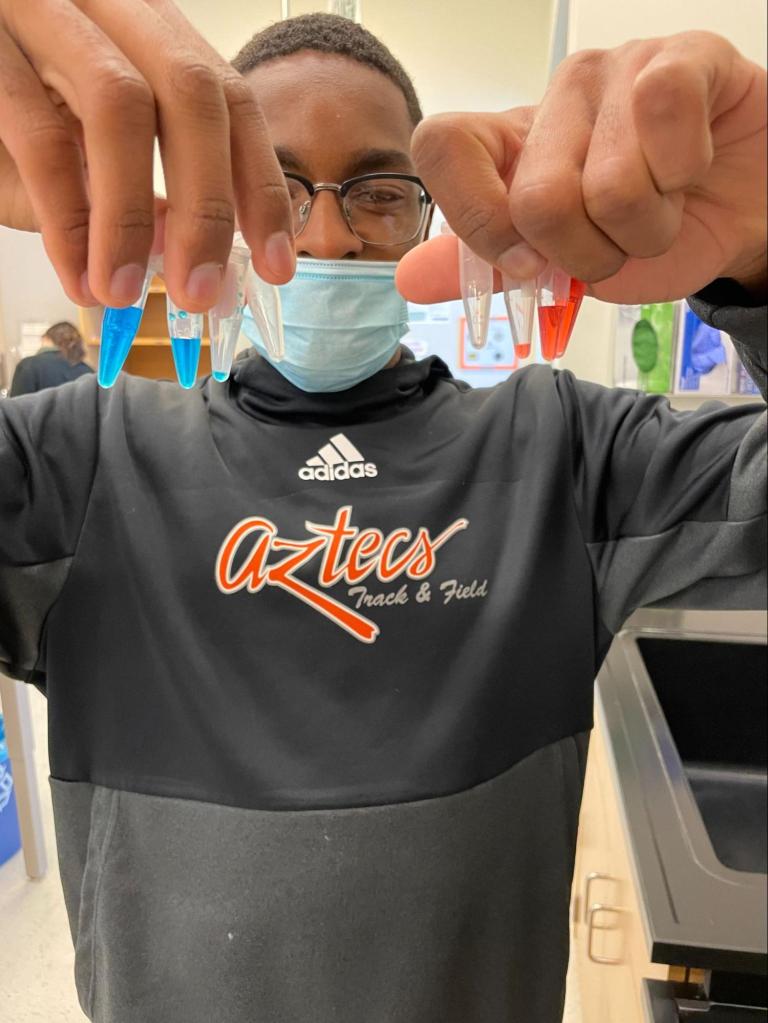

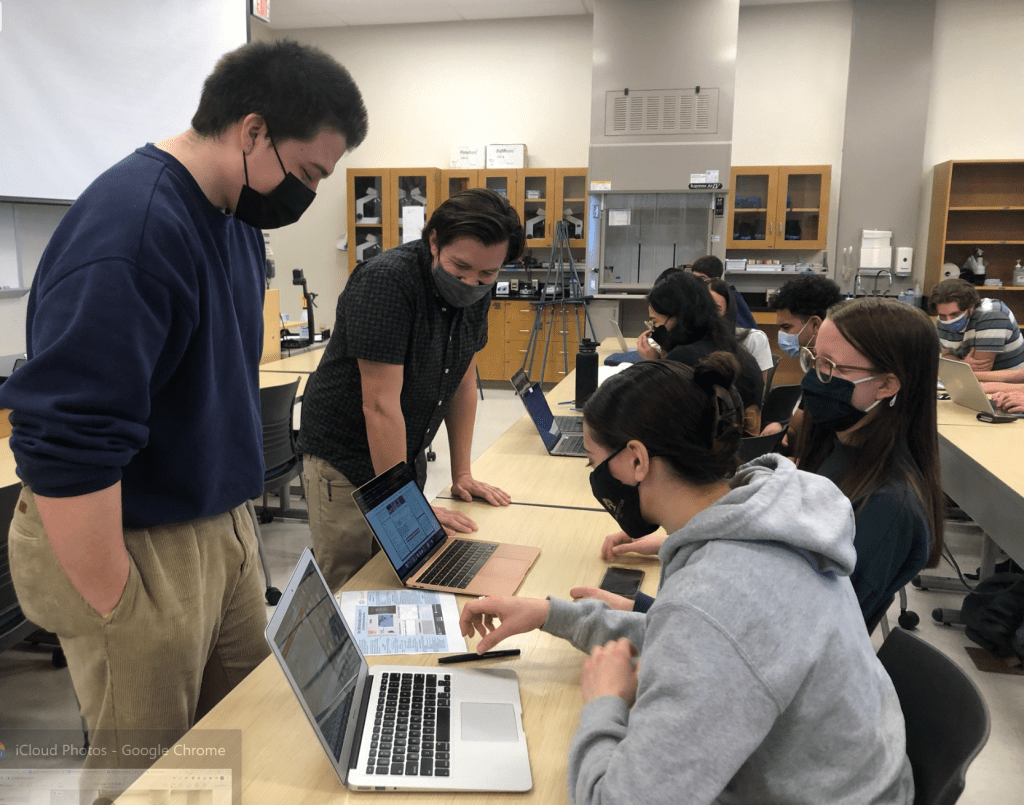

The Tucson Bee Collaborative aims to address this bottleneck in species identification. In 2019 Dr. Wendy Moore, Curator of the University of Arizona Insect Collection and Jennifer Katcher, Professor, Pima Community College, extended an invitation to the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum to collaborate—the Museum would provide unidentified bee specimens to UA and PCC students, and in exchange, students would provide the Museum with a DNA barcode for each bee. The success of this collaboration is what inspired creation of the Tucson Bee Collaborative (TBC), a partnership effort bringing together scientists of all ages and backgrounds to document and monitor the health of our native bees.

Through the TBC we aim to create a collection of every bee species in the region, its DNA barcode, and high-resolution images. Without doubt, this collection will advance our understanding of native bees and thus their conservation, but equally important is the work we do with students. Involving students in authentic research increases their sense of belonging in the scientific community and increases their likelihood of pursuing a STEM career. Additionally, focusing learning on Tucson’s exceptional bee diversity fosters students’ sense of place.

What started as a small study of bee diversity has grown into a cornerstone of the Desert Museum’s current scientific research and community programming. Barcoding has helped us identify many of our bees, as we hoped it would. What we didn’t realize is that we would be leading the effort to build the barcode reference library for Sonoran Desert bees!

As the barcode reference library grows, the 66 species matches from saguaro flowers will undoubtedly become hundreds of species matches, revealing a more complete picture of the central role of the iconic saguaro cactus in Sonoran Desert ecosystems and contributing important data that will help researchers better understand and conserve pollinators. As we build this barcode library of native bees, the need to collect bees for identification purposes will diminish, enabling researchers to rely on the reference libraries to make important ecological discoveries and connections. With these new connections and understandings, we are better prepared to protect our many diverse insect neighbors!

Thanks to the Principal Investigators of the saguaro flower eDNA study for their contributions!

- Mark Johnson, Jinelle Sperry, Aron Katz- ERDC-CERL (Engineering Research and Development Center-Construction Engineering Research Lab)

- Mark Davis, Brenda Molano-Flores (University of Illinois, Illinois Natural History Survey)

- Matthew Niemiller (University of Alabama in Huntsville)

Thank you for this, it was very interesting to learn more about the bee project!

LikeLike

Thanks for reading! We’re very excited about all of our progress so far and the conservation implications of this technology.

LikeLiked by 1 person